Light Works:

The Art of the Photogram

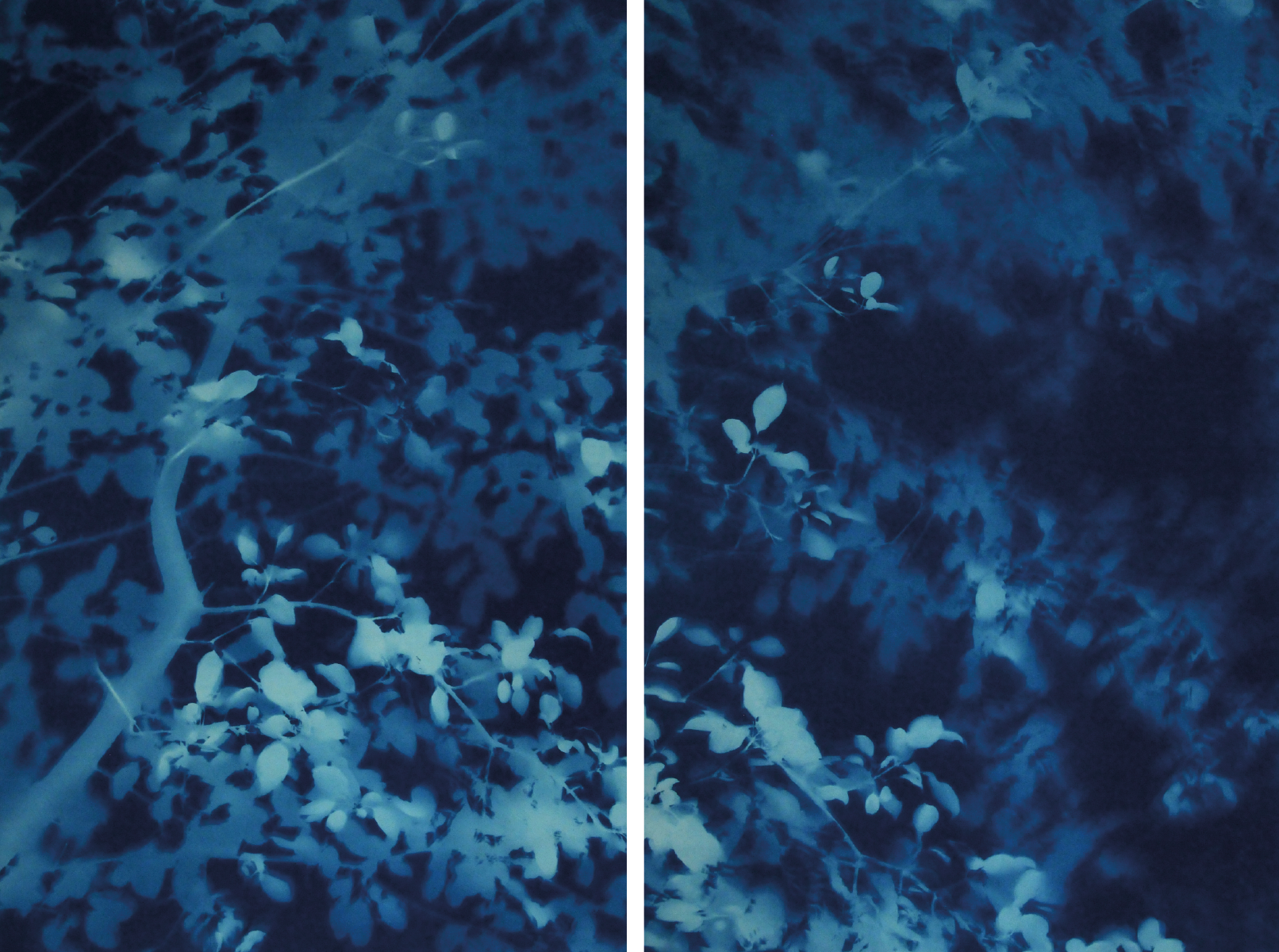

![Tom Fels, Arbor 8-10-14, Nos. 3 & 4, 2014]()

The Art of the Photogram

Paris Photo, Grand Palais, Paris

12 – 15 November 2015

ATLAS Gallery, London

27 November 2015 – 13 February 2016

Role:

Curator & Researcher

Team:

Ben Burdett, Gallery Director

Jim Edwards, Gallery Manager

With thanks to:

Floris Neusüss; Yorick Blumenfeld; Etherton Gallery, USA; Galerie Julian Sander, Germany; Galerie Kicken, Germany; HackelBury Fine Art, UK; Robert Klein Gallery, USA.

12 – 15 November 2015

ATLAS Gallery, London

27 November 2015 – 13 February 2016

Role:

Curator & Researcher

Team:

Ben Burdett, Gallery Director

Jim Edwards, Gallery Manager

With thanks to:

Floris Neusüss; Yorick Blumenfeld; Etherton Gallery, USA; Galerie Julian Sander, Germany; Galerie Kicken, Germany; HackelBury Fine Art, UK; Robert Klein Gallery, USA.

Using one of the first published photograms as a catalyst, Light Works examines the work of historical photographic protagonists to demonstrate the longstanding impact of the medium, starting with its origins as an artform in the early 20th century through to its continuing influence on contemporary practice.

Photograms are a cameraless photographic technique created by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive paper and exposing the arrangement to a light source. The resulting forms are defined by the varying ways in which the shape of an item restricts light reaching the paper beneath it; with factors such as sharpness and contrast wholly dependant on the opacity of the object and its proximity to the paper.The photogram process shares its chemistry with conventional photography but aesthetically the two forms are vastly different: photographs produce a familiar representation of our surroundings as we view them; conversely, photograms consist of inverted shadows that float abstractly in free space, with no perspective or horizon.

Due to the considerable ease of method, there are countless photogram experiments by both artists and amateurs alike, and whilst examples were created as early as the very first photographs by the likes of Fox-Talbot, it was from the late 1910s that its use as a means of artistic expression gained significant interest amongst avant-garde circles.

The exhibition begins by presenting the work of Christian Schad, who was creating cameraless work from around 1918, with one example printed in Tristan Tzara’s Dadaist periodical Dadaphone in 1920. Seen as both anti-painting due to its autonomy; and anti-photography due to a reluctance to conform to traditional photographic representation, his photograms using detritus from around the city delighted Dada sensibilities. Tzara termed these works Schadographs and deemed the importance of them so great that he later, unbeknownst to Schad, loaned five pieces for inclusion in MoMA’s first ever photography retrospective: Photography, 1839-1937.

Curator Beaumont Newhall went on to credit Schad in MoMA’s accompanying catalogue as the probable originator of the photogram as artform, even before other practitioners more commonly associated such as Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy; however, their contrasting schools of thought did drive the medium forward in two very different yet important directions: via the Surrealists in Paris, and with the Constructivists in Germany.Included in the exhibition are several works from a larger portfolio of 12 pieces by Man Ray, an artist who has become almost synonymous with the photogram and a significant contributor to both the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal. Whilst Man Ray never acknowledged Schad’s influence, it is most likely that he was aware of his work through Tzara’s advocacy. Utilising the same cameraless process, he termed his creations Rayographs.

Led by poet André Breton from 1924 through World War II, Surrealism refused more rational thought in preference of automatism which they believed brought them closer to a more authentic self; with photography acting as a perfect mechanical vehicle for such aims; its members practiced the experimental use of words and language and often used found objects and materials within their work. Whilst Surrealists valued dreams and the subconscious mind, these ideas were also present within the Dada movement which preceded it; however, the ideas of the former were intrinsically influenced by the texts and theories of psychologist Sigmund Freud.

At the same point in time, Moholy-Nagy was recruited by Walter Gropius for the Bauhaus in Weimar. Constructivism, and indeed the Bauhaus ideology looked to re-establish a relationship between art and industry through adherence to the practical application of aesthetics. Moholy-Nagy taught within the metal workshop and it was his outsider approach to photography that provided a plethora of inspiration, including the establishment of his New Vision (or Neue Optik), which served to affirm the camera as an extension of our vision; an optical prosthesis which allows one to see in an entirely new way. The exhibition includes a photogram from 1925, an important moment for Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus as both moved from Weimar to Dessau. Moholy-Nagy’s overwhelming significance and contribution to photography is impossible to summarise briefly.

A close peer and contemporary of Moholy-Nagy, György Kepes became familiar with the ideals of New Vision during frequent collaboration and infact, when the Bauhaus closed in Germany due to mounting political pressure, Moholy-Nagy immigrated to the UK and established a studio in London, where Kepes soon joined him. Moholy-Nagy went on to establish the Chicago School of Design in the USA in 1937, appointing Kepes as the head of department for Colour & Light. Kepes is often discussed in tandem with Moholy-Nagy but is an extraordinary artist entirely independent of their work together, with a definitively scientific approach to his practice. Kepes also thought of himself as a painter and he revived many older photographic processes to create more painterly effects. One such example presented in the exhibition is decalcomania, in which a viscous solution of ink and casein could be pressed between glass plates to produce unpredictable patterns. Whilst working in Chicago, Kepes went on to teach generations of influential graphic designers including Saul Bass, and later founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT.

Photograms by Floris Neusüss are presented alongside Moholy-Nagy for the first time since their work was jointly exhibited at Europa Centrum, Berlin, in 1966. Neusüss is one of the most important artists working with the photogram today, dedicating his entire career to the study of the medium; he has exhibited widely, written extensively and contributed to the curation and research of numerous exhibitions. Appointed in 1971 as Professor of Experimental Photography, Neusüss’ tenure at the University of Kassel, Germany, saw him establish Fotoforum as part of the curriculum, which consisted of a gallery, a collection and a platform for editorial output. He together with his wife Renate Heyne are the authority on the photogram, even co-authoring the catalogue raisoneé of Moholy-Nagy’s photogram works.

Neusüss has brought renewed ambition to the photogram process in both scale and visual treatment with his Körperbild series, first exhibited in the 1960s and included in this exhibition. He acknowledges the strong influence of both Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray on his own practice, and an example of allowing chance into his work is illustrated in a piece from his Gewitterbild series. Under the cover of darkness, Neusüss takes sheets of photographic paper out into his garden, placing it beneath trees and shrubs, where he waits patiently for the climactic moment when lightning strikes and exposes his paper, leaving a ghostly record of the foliage behind. Neusüss was one of 5 artists exhibited as part of the Shadow Catchers exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in 2011.

Artists exhibited:

Berenice Abbott, Werner Bischof, Erwin Blumenfeld, Richard Caldicott, Tom Fels, Peter Keetman, György Kepes, Alexander Khlebnikov, William Klein, Hans Kupelweiser, Lázló Maholy-Nagy, E.L.T Mesens, Floris Neusüss, Man Ray, Christian Schad, Pablo Picasso and Andre Villers.

Photograms are a cameraless photographic technique created by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive paper and exposing the arrangement to a light source. The resulting forms are defined by the varying ways in which the shape of an item restricts light reaching the paper beneath it; with factors such as sharpness and contrast wholly dependant on the opacity of the object and its proximity to the paper.The photogram process shares its chemistry with conventional photography but aesthetically the two forms are vastly different: photographs produce a familiar representation of our surroundings as we view them; conversely, photograms consist of inverted shadows that float abstractly in free space, with no perspective or horizon.

Due to the considerable ease of method, there are countless photogram experiments by both artists and amateurs alike, and whilst examples were created as early as the very first photographs by the likes of Fox-Talbot, it was from the late 1910s that its use as a means of artistic expression gained significant interest amongst avant-garde circles.

The exhibition begins by presenting the work of Christian Schad, who was creating cameraless work from around 1918, with one example printed in Tristan Tzara’s Dadaist periodical Dadaphone in 1920. Seen as both anti-painting due to its autonomy; and anti-photography due to a reluctance to conform to traditional photographic representation, his photograms using detritus from around the city delighted Dada sensibilities. Tzara termed these works Schadographs and deemed the importance of them so great that he later, unbeknownst to Schad, loaned five pieces for inclusion in MoMA’s first ever photography retrospective: Photography, 1839-1937.

Curator Beaumont Newhall went on to credit Schad in MoMA’s accompanying catalogue as the probable originator of the photogram as artform, even before other practitioners more commonly associated such as Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy; however, their contrasting schools of thought did drive the medium forward in two very different yet important directions: via the Surrealists in Paris, and with the Constructivists in Germany.Included in the exhibition are several works from a larger portfolio of 12 pieces by Man Ray, an artist who has become almost synonymous with the photogram and a significant contributor to both the Dada and Surrealist movements, although his ties to each were informal. Whilst Man Ray never acknowledged Schad’s influence, it is most likely that he was aware of his work through Tzara’s advocacy. Utilising the same cameraless process, he termed his creations Rayographs.

Led by poet André Breton from 1924 through World War II, Surrealism refused more rational thought in preference of automatism which they believed brought them closer to a more authentic self; with photography acting as a perfect mechanical vehicle for such aims; its members practiced the experimental use of words and language and often used found objects and materials within their work. Whilst Surrealists valued dreams and the subconscious mind, these ideas were also present within the Dada movement which preceded it; however, the ideas of the former were intrinsically influenced by the texts and theories of psychologist Sigmund Freud.

At the same point in time, Moholy-Nagy was recruited by Walter Gropius for the Bauhaus in Weimar. Constructivism, and indeed the Bauhaus ideology looked to re-establish a relationship between art and industry through adherence to the practical application of aesthetics. Moholy-Nagy taught within the metal workshop and it was his outsider approach to photography that provided a plethora of inspiration, including the establishment of his New Vision (or Neue Optik), which served to affirm the camera as an extension of our vision; an optical prosthesis which allows one to see in an entirely new way. The exhibition includes a photogram from 1925, an important moment for Moholy-Nagy and the Bauhaus as both moved from Weimar to Dessau. Moholy-Nagy’s overwhelming significance and contribution to photography is impossible to summarise briefly.

A close peer and contemporary of Moholy-Nagy, György Kepes became familiar with the ideals of New Vision during frequent collaboration and infact, when the Bauhaus closed in Germany due to mounting political pressure, Moholy-Nagy immigrated to the UK and established a studio in London, where Kepes soon joined him. Moholy-Nagy went on to establish the Chicago School of Design in the USA in 1937, appointing Kepes as the head of department for Colour & Light. Kepes is often discussed in tandem with Moholy-Nagy but is an extraordinary artist entirely independent of their work together, with a definitively scientific approach to his practice. Kepes also thought of himself as a painter and he revived many older photographic processes to create more painterly effects. One such example presented in the exhibition is decalcomania, in which a viscous solution of ink and casein could be pressed between glass plates to produce unpredictable patterns. Whilst working in Chicago, Kepes went on to teach generations of influential graphic designers including Saul Bass, and later founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT.

Photograms by Floris Neusüss are presented alongside Moholy-Nagy for the first time since their work was jointly exhibited at Europa Centrum, Berlin, in 1966. Neusüss is one of the most important artists working with the photogram today, dedicating his entire career to the study of the medium; he has exhibited widely, written extensively and contributed to the curation and research of numerous exhibitions. Appointed in 1971 as Professor of Experimental Photography, Neusüss’ tenure at the University of Kassel, Germany, saw him establish Fotoforum as part of the curriculum, which consisted of a gallery, a collection and a platform for editorial output. He together with his wife Renate Heyne are the authority on the photogram, even co-authoring the catalogue raisoneé of Moholy-Nagy’s photogram works.

Neusüss has brought renewed ambition to the photogram process in both scale and visual treatment with his Körperbild series, first exhibited in the 1960s and included in this exhibition. He acknowledges the strong influence of both Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray on his own practice, and an example of allowing chance into his work is illustrated in a piece from his Gewitterbild series. Under the cover of darkness, Neusüss takes sheets of photographic paper out into his garden, placing it beneath trees and shrubs, where he waits patiently for the climactic moment when lightning strikes and exposes his paper, leaving a ghostly record of the foliage behind. Neusüss was one of 5 artists exhibited as part of the Shadow Catchers exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in 2011.

Artists exhibited:

Berenice Abbott, Werner Bischof, Erwin Blumenfeld, Richard Caldicott, Tom Fels, Peter Keetman, György Kepes, Alexander Khlebnikov, William Klein, Hans Kupelweiser, Lázló Maholy-Nagy, E.L.T Mesens, Floris Neusüss, Man Ray, Christian Schad, Pablo Picasso and Andre Villers.